This post is not for the faint of heart.

I have been to a number of Holocaust sites and museums: Auschwitz, Anna Frank House in Amsterdam, Holocaust Museum in Washington, Jewish Museum and the Memorial to the Murdered Jews in Berlin. These museums leave me with the feeling of deep loss, deep emptiness, as if I crash into a concrete wall, which signifies the impossibilty of quite grasping the abyss of pain. That very feeling of abyss came back to me in this museum, probably the most important in Phnom Penh.

In 1975 the revolutionary troops of Khmer Rouge headed by Pol Pot broke the resistance of Cambodia’s reactionary government and took Phnom Penh. Immediately an order followed: all city dwellers were to leave the cities and proceed to villages all around Cambodia. The initial explanation was the evacuation from the coming American bombings, and it was said to be only for three days. In reality the reasons were of a fundamental nature: Pol Pot’s ideology, inspired by Mao’s cultural revolution, saw only peasants as true participants of the new society. Therefore the rest of the population was to be turned into peasants.

Former city inhabitants were referred to as “new people” and had a lower status in the new villages than the peasants – the “basic people”. The whole country, from former elites, professionals, intellectuals, to peasants, toiled non-stop for 12 hours a day in the rice fields. The slightest protest led to being sent by Angkar for “education”. Angkar, the name of the ruling organ of the communist Cambodia at the time of Khmer Rouge, means simply “organisation”. The very existence of the communist party was kept secret for a long time.

One of the 300 macabre “education” camps created by Angkar can be visited in Phnom Penh. It was called prison S21 and was located in a complex of buildings that formerly served as a school. Today it houses the Genocide Museum of Tuol Sleng:

21000 people went through S21 during its 4 years of functioning. Only 7 persons survived. The rest, after many months of detention and inhuman torture, were sent to the Killing Fields of Cheung Ek and destroyed there. When the Vietnamese troops liberated Phnom Penh in 1979, they found 14 bodies in the prison, of people murdered just before their arrival.

Overall, up to 2 million people were killed, which represented about a third of the population at the time.

The open balconies of the school were covered with barbed wire, to prevent the prisoners from escaping the horror by jumping out:

Inside the school’s classes, narrow cells were built of rough brick:

On the walls of the museum there are paintings of one of the survivors, where the torture scenes are depicted. I did not photograph these disturbing paintings. However I consider them absolutely necessary. The very fact of these crimes is not easy to prove in today’s Cambodia. The overwhelming majority of the prisoners of S21 was destroyed, and there is virtually nobody to tell about the crimes in first person. The perpetrators of the crimes deny their guilt.

Some classrooms were specifically used for torture. One can see some of the torture tools there:

The prisoners were chained to the iron beds.

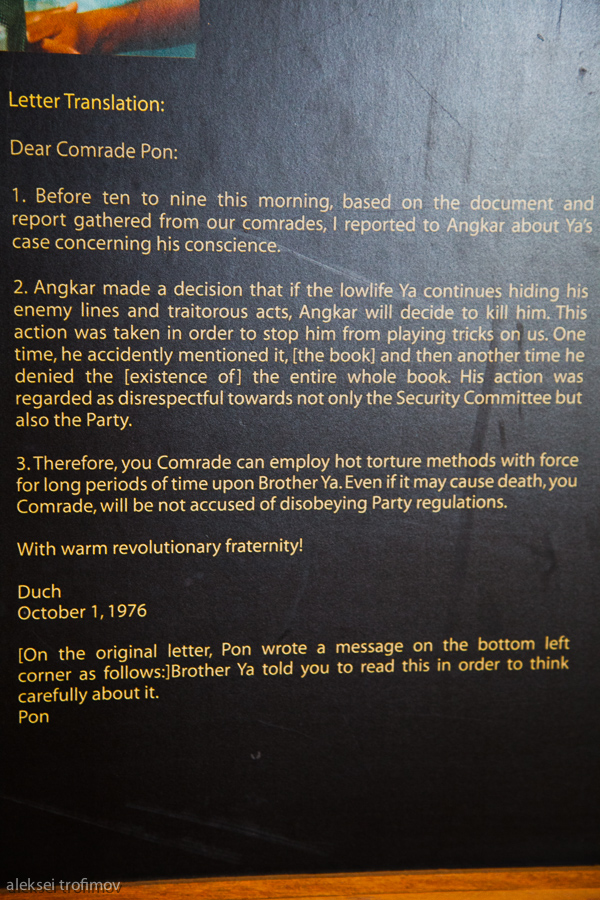

The English translation of the order of the infamous prison commander, Comrade Duch. The handwritten Khmer original hangs next.

Duch is the only Khmer Rouge leader that has been convicted of crimes against humanity. The process of over a number of other leaders is ongoing.

The Killing Field of Cheung Ek is about 15 km from Phnom Penh. Every killing field was attached to a particular prison. Cheung Ek was attached to S21. The prisoners sentenced to death were driven to the field and killed there. Normally it was done at night. To save bullets people were killed by hacks or other simple tools. One by one they were lead out of the hut with their eyes closed with a scarf, asked to stand on their knees, and then hit to the back of the head. The body then fell to the already dug pit. Nobody checked if the person was dead or just lost consciousness. One can see many such pits in the Killing Fields.

However some pits are still unopened. During the rain season the earth often reveals fragments of bones or teeth. A visitor to Cheung Ek can see them too.

From four sides on this tree were placed the translators, which played loud communist songs to drown out the groans.

Please don’t walk through the mass grave.

In the middle of the Killing Field a Buddhist temple is erected which is devoted to the memory of the prisoners. Inside the temple there are 16 levels, each filled with the remnants.

The lower level.

Tragically, the history of humanity includes many cases of genocide. Some of these are universally recognised, others are controversial:

- The Holocaust;

- simultaneously with the Holocaust, the genocide of the Roma, homosexuals and other groups;

- genocide of Armenians, Greeks and Assyrians during the breakup of the Ottoman Empire;

- genocide of American Indians and Pacific Island aborigens;

- genocide in the Congo during the colonial times;

- political genocide in the USSR;

- genocide in Rwanda;

- finally, Cambodian genocide.

A couple of days later I was driving in tuk tuk on the outskirts of Phnom Penh. We passed a deserted wasteland. No person could be seen. But for reasons unknown the sugary Cambodian music was playing loud, filling the space all around. I was horrified.